Tongue lacerations are a common occurrence in clinical practice and can result from various causes, including falls, trauma, or seizures. However, not all tongue lacerations require surgical repair, as the tongue possesses an excellent blood supply and natural healing abilities.

Indications for Suturing

1. Large lacerations (>2cm) or extensive wounds, especially when the tongue is at rest.

2. Cases of uncontrolled bleeding.

3. Non-gaping wounds.

4. Anterior split tongue.

Lacerations That May Not Require Repair

1. Non-gaping lacerations on the dorsum of the tongue.

2. Gaping lacerations on the dorsum of the tongue measuring ≤2 cm in length that naturally approximate when the tongue is at rest.

3. Consideration for delayed repair: Tongue lacerations older than 24 hours should be left open for secondary intention healing due to the increased risk of infection.

- Local Anesthesia

Prior to the procedure, administer proper local anesthesia to minimize patient discomfort. This can be achieved through direct local infiltration or an inferior alveolar nerve block.

- Irrigation and Debridement

Examine the wound thoroughly for fractured teeth or foreign objects and remove them if present. Then, meticulously irrigate the wound with approximately 50 to 100 mL of normal saline using a 30-mL syringe and an 18-gauge angiocatheter or splash guard.

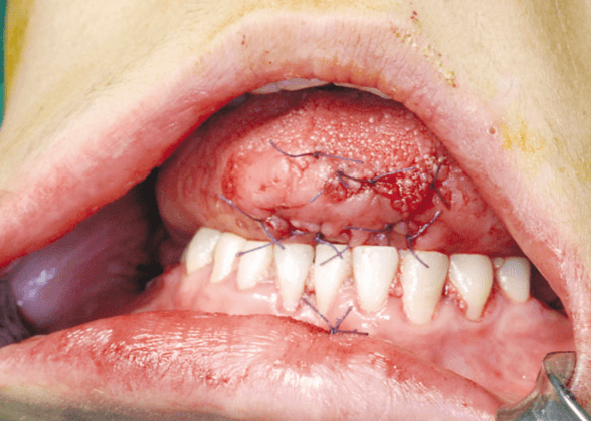

Procedure

– For dorsal tongue lacerations, use 3-0 or 4-0 absorbable sutures (e.g., chromic gut or Vicryl) to take full-thickness bites of both the mucosal surface and the lingual muscle to prevent dehiscence.

– Through-and-through lacerations require a two- or three-layered closure using 4-0 or 5-0 chromic gut or Vicryl. Begin with suturing the deep muscle, followed by the submucosa and mucosa.

– When dealing with tip or large lateral border tongue lacerations, ensure meticulous margin approximation, avoid tissue edge overlap, and place sutures loosely to accommodate potential swelling. Tie each suture securely with at least four square knots to withstand the tongue’s constant motion.

- Tetanus Prophylaxis

Consider administering tetanus prophylaxis in cases of dirty wounds or high-risk situations.

- Prophylactic Antibiotics

Most tongue lacerations heal without the need for prophylactic antibiotics, especially small ones that are not sutured. However, high-risk lacerations requiring antibiotic coverage include heavily contaminated wounds, delayed presentations (>24 hours), immunocompromised individuals, and lacerations resulting from animal or human bites.

Antibiotic treatment should cover Gram-positive and anaerobic bacteria, with options such as amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cephalexin, or clindamycin, taken orally for five days.

- Complications

Within the first 48 hours, complications may include edema, hemorrhage, and aspiration of saliva and blood.

Manage mild lingual edema with cold applications (e.g., ice chips, Popsicles).

In more severe cases with no contraindications, consider a single dose of intravenous (IV) steroids (e.g., Decadron 0.6 mg/kg), and hospitalization may be necessary to ensure airway patency.

Other potential complications of tongue lacerations include dehiscence and infection. To prevent dehiscence, place sutures loosely to accommodate swelling.

- Discharge Instructions

Post-treatment instructions are crucial for patient care and should include:

– A soft food diet for two to three days to promote rapid healing.

– Drinking or gently rinsing the mouth with water after eating.

– Frequent application of cold (e.g., sucking on ice chips) to prevent tongue swelling.

– Caution when using a toothbrush, especially in young children.

– Monitoring for signs of wound infections, such as fever, increased pain, and swelling.

Additional Note

While it’s often recommended to avoid sucking on a straw, there is insufficient evidence to suggest that it significantly increases the risk of bleeding or delayed healing in patients with tongue lacerations.