Hemochromatosis is a genetic or acquired condition characterized by excessive iron accumulation in the body, leading to tissue damage and organ dysfunction.

It is primarily associated with mutations in the HFE gene but can also be secondary to other conditions.

Types of Hemochromatosis

- Hereditary Hemochromatosis (HH)

- Type 1 (Classic Hemochromatosis): Most common form, associated with HFE gene mutations (C282Y and H63D mutations). It usually presents in adulthood.

- Type 2 (Juvenile Hemochromatosis): Caused by mutations in the HJV (hemojuvelin) or HAMP (hepcidin) genes. It presents in adolescence with more severe symptoms.

- Type 3 (Transferrin Receptor-2 Hemochromatosis): Results from mutations in the TFR2 gene, presenting similarly to Type 1 but usually at a younger age.

- Type 4 (Ferroportin Disease): An autosomal dominant condition caused by mutations in the ferroportin gene (SLC40A1). It leads to increased iron storage but is less common.

- Secondary Hemochromatosis

- Results from increased iron intake, repeated blood transfusions, chronic liver diseases (e.g., alcoholic liver disease, hepatitis), or conditions like thalassemia and sideroblastic anemia.

Pathophysiology

- The body normally absorbs about 1-2 mg of iron daily to replace iron lost through desquamation of cells from the gut, skin, and genitourinary tract.

- In hemochromatosis, mutations affect iron-regulatory mechanisms, leading to:

- Increased intestinal iron absorption: Enhanced absorption occurs due to decreased levels of hepcidin, a key regulator of iron homeostasis produced by the liver. Hepcidin inhibits iron absorption by binding to ferroportin, an iron transporter in enterocytes and macrophages. In hemochromatosis, hepcidin suppression allows for unregulated iron entry into the circulation.

- Iron Overload in Organs: Excess iron is deposited in various tissues, including the liver, heart, pancreas, joints, and endocrine glands. The accumulation generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to cellular damage, fibrosis, and organ failure.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical manifestations vary with the degree and duration of iron overload. Symptoms may be absent or non-specific in early stages and more pronounced in advanced disease.

- Early Symptoms

- Fatigue, weakness, joint pain (especially the hands, knees, and hips).

- Non-specific abdominal pain.

- Organ-Specific Manifestations

- Liver: Hepatomegaly, elevated liver enzymes, cirrhosis, and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Heart: Cardiomyopathy, leading to arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, or restrictive heart disease.

- Pancreas: Diabetes mellitus (known as “bronze diabetes” due to the combination of diabetes and skin hyperpigmentation).

- Skin: Hyperpigmentation, giving a “bronze” appearance due to melanin and iron deposition.

- Endocrine Dysfunction: Hypogonadism (decreased libido, impotence, amenorrhea), hypothyroidism.

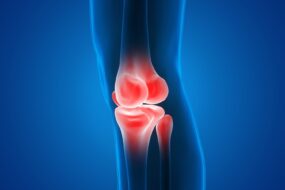

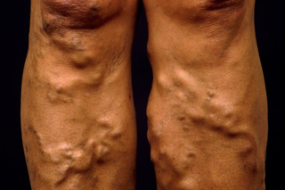

- Joints: Arthropathy due to iron deposition, often resembling osteoarthritis but commonly affecting the second and third metacarpophalangeal joints.

- Advanced Symptoms

- Liver failure, diabetes complications, heart failure, and severe joint disease.

Diagnosis

- Laboratory Tests

- Serum Ferritin: Elevated levels (>300 ng/mL in men, >200 ng/mL in women) indicate iron overload but can also be raised in other inflammatory or liver conditions.

- Transferrin Saturation: Elevated (>45%) indicates increased iron absorption and is more specific for hemochromatosis.

- Serum Iron and Total Iron-Binding Capacity (TIBC): Increased serum iron levels with low TIBC.

- Genetic Testing: HFE mutation analysis is used to confirm hereditary hemochromatosis, particularly C282Y and H63D mutations.

- Imaging

- MRI: Can measure liver iron concentration non-invasively. Useful for assessing iron overload in the liver and heart.

- Liver Biopsy: May be necessary for patients with advanced disease or unclear diagnosis. Prussian blue staining highlights iron deposits.

- Other Tests

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) and Echocardiogram: To evaluate cardiac function in patients with suspected iron-related cardiomyopathy.

- Endocrine Evaluation: Assess for diabetes, hypogonadism, or other endocrine dysfunction.

Management

- Therapeutic Phlebotomy

- The mainstay of treatment for reducing iron overload.

- Procedure: 500 mL of blood is removed weekly (equivalent to 200-250 mg of iron). Once ferritin levels reach 50-100 ng/mL, maintenance phlebotomy is performed every 2-4 months.

- Goal: Maintain serum ferritin levels between 50-100 ng/mL and transferrin saturation below 45%.

- Regular phlebotomy can prevent or reverse many symptoms of hemochromatosis, including fatigue, skin hyperpigmentation, and organ dysfunction.

- Iron Chelation Therapy

- Used when phlebotomy is contraindicated (e.g., anemia or poor venous access).

- Drugs: Deferoxamine, deferasirox, and deferiprone are iron chelators used to reduce body iron levels.

- Chelation is less effective than phlebotomy but necessary in patients with secondary iron overload due to transfusions.

- Management of Organ Damage

- Liver Disease: Monitor for liver function and screen for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Liver transplantation may be needed in advanced cases.

- Heart Disease: Treat heart failure with standard therapy, including diuretics, ACE inhibitors, or beta-blockers. Cardiac MRI can guide iron chelation if needed.

- Diabetes Management: Use insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents as indicated.

- Joint Symptoms: Manage with NSAIDs, physical therapy, and joint injections. Joint replacement surgery may be necessary for advanced arthropathy.

- Dietary Modifications

- Avoid excess iron intake (e.g., red meat) and vitamin C supplements, as vitamin C enhances iron absorption.

- Limit alcohol consumption, which can exacerbate liver damage.

Complications

- Liver Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Chronic iron overload leads to progressive fibrosis and increases the risk of liver cancer.

- Heart Failure and Arrhythmias: Due to iron deposition in cardiac tissues.

- Endocrine Disorders: Diabetes, hypothyroidism, and hypogonadism are common in advanced disease.

- Arthropathy: Chronic joint pain and deformities can occur.

Monitoring and Follow-Up

- Regular Ferritin and Transferrin Saturation: Every 3-6 months for monitoring iron levels and guiding phlebotomy frequency.

- Liver Ultrasound and AFP Testing: For patients with cirrhosis, screen for hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Cardiac Evaluation: Regular assessment for symptoms of heart failure or arrhythmias.

Prognosis

- Early diagnosis and treatment, especially before the onset of organ damage, significantly improve outcomes.

- Regular phlebotomy can prevent complications and normalize life expectancy in most patients with hereditary hemochromatosis.

- For those with advanced disease, the prognosis depends on the extent of organ involvement.