- Home

- INTERNAL MEDICINE

- Shigellosis (Bacillary Dysente ...

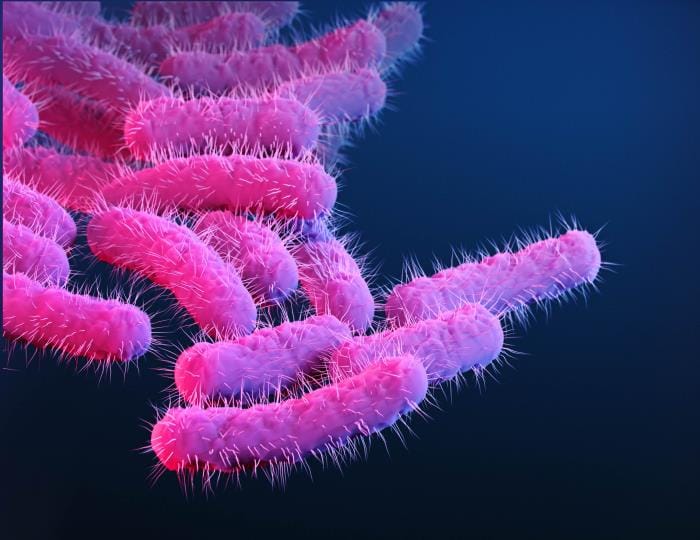

Shigellosis is an acute intestinal infection caused by Shigella species, which are gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic bacteria. It is a major cause of bacillary dysentery worldwide, particularly in areas with poor sanitation and overcrowding. Shigellosis can present as a self-limited disease or a severe, life-threatening condition, especially in children, the elderly, or immunocompromised individuals.

Etiology and Pathophysiology:

- Shigella species are divided into four major groups:

- Group A: Shigella dysenteriae (most severe, can produce Shiga toxin)

- Group B: Shigella flexneri (common in developing countries)

- Group C: Shigella boydii (less common)

- Group D: Shigella sonnei (predominant in industrialized nations)

The pathogenesis of shigellosis involves:

- Ingestion of the organism: Shigella bacteria are transmitted via the fecal-oral route, commonly through contaminated food, water, or direct person-to-person contact.

- Colonization of the colon: The bacteria attach to and invade the colonic mucosa, primarily in the distal ileum and colon. They penetrate the intestinal epithelial cells through M cells located in Peyer’s patches.

- Intracellular multiplication and spread: After invading the epithelial cells, Shigella bacteria multiply within the cytoplasm and spread to adjacent cells, causing cell death, tissue damage, and an intense inflammatory response.

- Shiga toxin production (in S. dysenteriae type 1): This exotoxin inhibits protein synthesis in host cells, leading to further epithelial damage and complications like hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS).

Epidemiology:

- Shigellosis is prevalent worldwide, with higher incidence in tropical and subtropical regions where sanitation is poor.

- High-risk populations include:

- Children under five years of age

- Elderly individuals

- Immunocompromised patients (e.g., HIV/AIDS)

- Institutionalized populations (e.g., prisons, daycares)

- Travelers to endemic regions

Clinical Manifestations:

The clinical presentation varies depending on the Shigella species and host factors but typically includes:

- Incubation period: Ranges from 1 to 7 days, usually 2-3 days.

- Initial symptoms: Include fever, malaise, and abdominal cramps. This may be followed by watery diarrhea.

- Dysenteric phase: Characterized by frequent, small-volume, bloody, and mucoid stools accompanied by severe abdominal cramps and tenesmus (painful straining during defecation). The dysentery is a result of mucosal invasion and inflammation in the colon.

- Complications:

- Severe dehydration: Due to fluid loss, especially in young children and the elderly.

- Sepsis: More common in malnourished individuals or those with compromised immune systems.

- Hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS): Particularly associated with S. dysenteriae type 1 and characterized by acute kidney injury, hemolytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia.

- Toxic megacolon: Rare but serious, involving severe colonic distention.

- Neurological complications: Such as seizures, which are more common in children.

Diagnosis:

- Stool culture:

- The gold standard for diagnosing shigellosis, with isolation of Shigella species confirming the infection.

- Sensitivity testing should be performed to guide antibiotic therapy due to increasing antibiotic resistance.

- Stool microscopy:

- May show leukocytes and red blood cells, suggesting an invasive bacterial pathogen.

- PCR testing and molecular assays:

- Detects Shigella DNA and can be useful in settings where culture facilities are limited.

- Serologic tests:

- Generally not used in routine diagnosis but may have epidemiological value.

Management:

- Rehydration therapy:

- The cornerstone of treatment, particularly for patients with moderate to severe dehydration.

- Oral rehydration salts (ORS) are preferred for mild to moderate dehydration.

- Intravenous fluids are indicated in severe dehydration or when oral rehydration is not feasible.

- Antibiotic therapy:

- Shortens the duration of illness, reduces transmission, and prevents complications.

- Empiric therapy should consider local resistance patterns:

- Ciprofloxacin (500 mg orally twice daily for 3 days): Widely used in adults but increasingly encountering resistance.

- Azithromycin (500 mg orally once daily for 3 days): An alternative, especially in children.

- Ceftriaxone (2 g intravenously once daily for 5 days): For severe cases or when oral therapy is not possible.

- Alternative antibiotics: Such as pivmecillinam or fosfomycin, may be used based on susceptibility.

- Avoiding antimotility agents: Such as loperamide, as they may worsen the disease by slowing fecal clearance of the pathogen.

- Management of complications:

- Severe dehydration: Requires prompt fluid resuscitation with isotonic fluids (e.g., normal saline or Ringer’s lactate).

- Hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS): Managed with supportive care, including dialysis and blood transfusions as needed.

- Toxic megacolon: Requires prompt medical and potentially surgical management.

Complications:

- Malnutrition and growth retardation: Particularly in children with repeated or chronic infections.

- Post-infectious sequelae: Including reactive arthritis, which may develop weeks after the infection, especially in individuals carrying the HLA-B27 allele.

- Chronic diarrhea: May occur in patients with malnutrition or underlying gastrointestinal diseases.

Prevention and Control:

- Improving sanitation and hygiene:

- Handwashing with soap and water is crucial, especially in endemic areas and institutions.

- Safe disposal of human waste and provision of clean drinking water.

- Food safety:

- Proper cooking of food, avoiding raw or contaminated foods, especially in areas with known outbreaks.

- Vaccination:

- There is no widely available vaccine for shigellosis, but several candidates are under investigation, including oral and injectable vaccines targeting various Shigella serotypes.

- Public health measures:

- Outbreak surveillance and timely interventions in cases of outbreaks, particularly in healthcare settings, schools, and refugee camps.

Advanced Considerations

- Antimicrobial resistance: Shigella species are increasingly resistant to common antibiotics (e.g., ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ampicillin), complicating treatment choices. Understanding local resistance patterns is essential for empirical therapy.

- Treatment in special populations:

- In pregnant women, azithromycin is generally preferred due to its safety profile.

- HIV-infected patients may require more aggressive treatment and monitoring for complications.

- Novel therapeutic approaches: The use of probiotics, bacteriophage therapy, and anti-inflammatory agents is under investigation for improving treatment outcomes.

Prognosis:

- Mild cases: Typically resolve within a week with supportive care and antibiotics.

- Severe cases: Have a higher risk of complications, especially in malnourished children, the elderly, and those with comorbidities.

- Recurrent or chronic shigellosis: Can occur in immunocompromised individuals, requiring long-term management strategies.