- Home

- INTERNAL MEDICINE

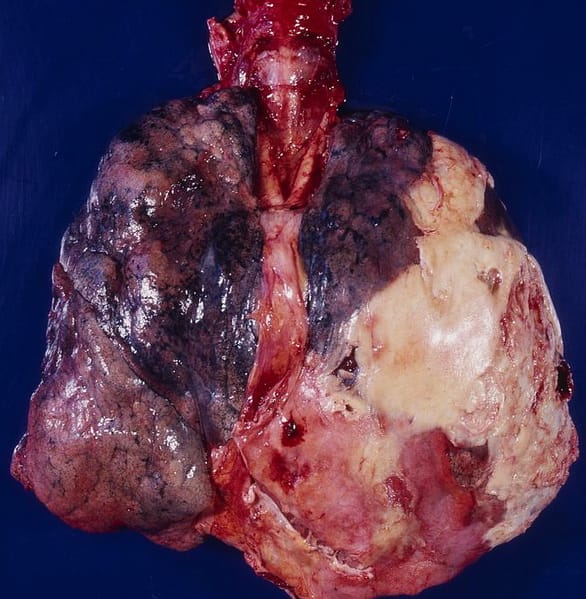

- Empyema

Empyema, also known as pyothorax or pleural empyema, is a collection of pus within the pleural cavity resulting from infection. It is typically associated with pneumonia but can also arise due to trauma, surgery, or underlying lung conditions.

Pathophysiology:

Empyema develops in three stages:

- Exudative Phase: The initial stage involves the accumulation of sterile fluid in the pleural space, characterized by a high protein content and low cellularity.

- Fibrinopurulent Phase: As the infection progresses, bacteria and white blood cells infiltrate the pleural fluid, leading to pus formation. Fibrin deposition occurs, resulting in loculated fluid collections.

- Organizing Phase: Fibroblast proliferation leads to thick pleural peel formation, which may trap the lung and impair re-expansion, potentially causing chronic empyema.

Etiology:

Empyema often results from:

- Bacterial pneumonia (most common): Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, including Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and Gram-negative organisms such as Klebsiella pneumoniae.

- Post-surgical infections: Following thoracic surgeries.

- Trauma: Penetrating chest injuries can introduce pathogens into the pleural space.

- Esophageal rupture (Boerhaave syndrome) or diaphragmatic hernia.

- Intra-abdominal infections: Transdiaphragmatic spread.

Risk factors include underlying chronic lung diseases, immunosuppression, diabetes, alcoholism, and age extremes.

Clinical Presentation:

Patients may present with:

- Symptoms: Fever, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, cough (productive or non-productive), and systemic signs of sepsis. Symptoms may have an insidious onset, especially in chronic cases.

- Physical Examination: Decreased breath sounds, dullness to percussion, and decreased tactile fremitus on the affected side. Pleural friction rub may be present.

Diagnostic Approach:

- Imaging Studies:

- Chest X-ray: Shows pleural fluid collection with blunting of the costophrenic angle. In lateral decubitus views, fluid layers suggest free-flowing effusion.

- Chest CT Scan: Preferred for identifying loculated fluid collections, pleural thickening, and underlying lung pathology. Helps guide drainage procedures.

- Ultrasound: Useful for identifying fluid pockets for thoracentesis.

- Pleural Fluid Analysis:

- Diagnostic Thoracentesis: Essential for confirming empyema. Pleural fluid typically shows:

- pH < 7.2

- Glucose < 40 mg/dL

- Elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), often >1000 IU/L

- Polymorphonuclear leukocytes predominance

- Microbiological Studies: Culture, Gram stain, and PCR for specific pathogens.

- Diagnostic Thoracentesis: Essential for confirming empyema. Pleural fluid typically shows:

- Laboratory Tests:

- Complete blood count (CBC): Leukocytosis may indicate infection.

- Inflammatory markers: Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

Management:

Treatment is based on the stage of empyema, clinical status, and underlying cause.

- Antibiotic Therapy:

- Empiric coverage should target common pathogens, including Streptococcus spp., Staphylococcus aureus, and Gram-negative organisms.

- Initial Empiric Therapy: Intravenous (IV) antibiotics such as:

- Ceftriaxone (2g IV once daily) + Metronidazole (500mg IV every 8 hours) for anaerobic coverage.

- Piperacillin-tazobactam (4.5g IV every 6 hours) for broader coverage.

- In cases of suspected MRSA: Vancomycin (15-20 mg/kg IV every 8-12 hours), aiming for a trough level of 15-20 µg/mL.

- Duration of Therapy: Generally 3-4 weeks, tailored based on clinical response and radiological improvement.

- Drainage Procedures:

- Thoracentesis: Effective for early-stage, free-flowing effusions.

- Chest Tube Insertion (Tube Thoracostomy): Required for loculated or fibrinopurulent empyema. Use of a small-bore catheter (10-14 Fr) may be considered, though larger-bore catheters (20-28 Fr) may be necessary for thick pus.

- Intrapleural Fibrinolytic Therapy: Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) plus deoxyribonuclease (DNase) (e.g., tPA 10 mg + DNase 5 mg intrapleurally twice daily for 3 days) may be used to break down loculations.

- Surgical Intervention:

- Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS): Indicated for patients with failure of drainage and fibrinolytic therapy. Allows for decortication and removal of the thick pleural peel.

- Open Thoracotomy with Decortication: Considered in chronic empyema where thick fibroelastic tissue entraps the lung.

- Open Window Thoracostomy: An option for debilitated patients where definitive surgery poses a high risk.

Post-Treatment Monitoring and Complications:

- Serial imaging (chest X-rays or CT scans) is essential to monitor resolution.

- Pulmonary function tests may be indicated to assess lung recovery post-resolution.

- Potential complications include bronchopleural fistula, fibrothorax, and lung entrapment.

Chronic Empyema Considerations:

- Chronic empyema is defined by the persistence of symptoms or radiologic findings beyond 3 weeks.

- Management may involve a combination of long-term antibiotics, repeated drainage, and possibly, surgery.

- The approach should be multidisciplinary, involving pulmonologists, infectious disease specialists, and thoracic surgeons.

Prognosis:

- The prognosis largely depends on prompt diagnosis, the severity of the infection, the presence of comorbidities, and timely intervention.

- Mortality rates can be significant in cases with advanced sepsis, delayed treatment, or in patients with underlying immunosuppression.