- Home

- INTERNAL MEDICINE

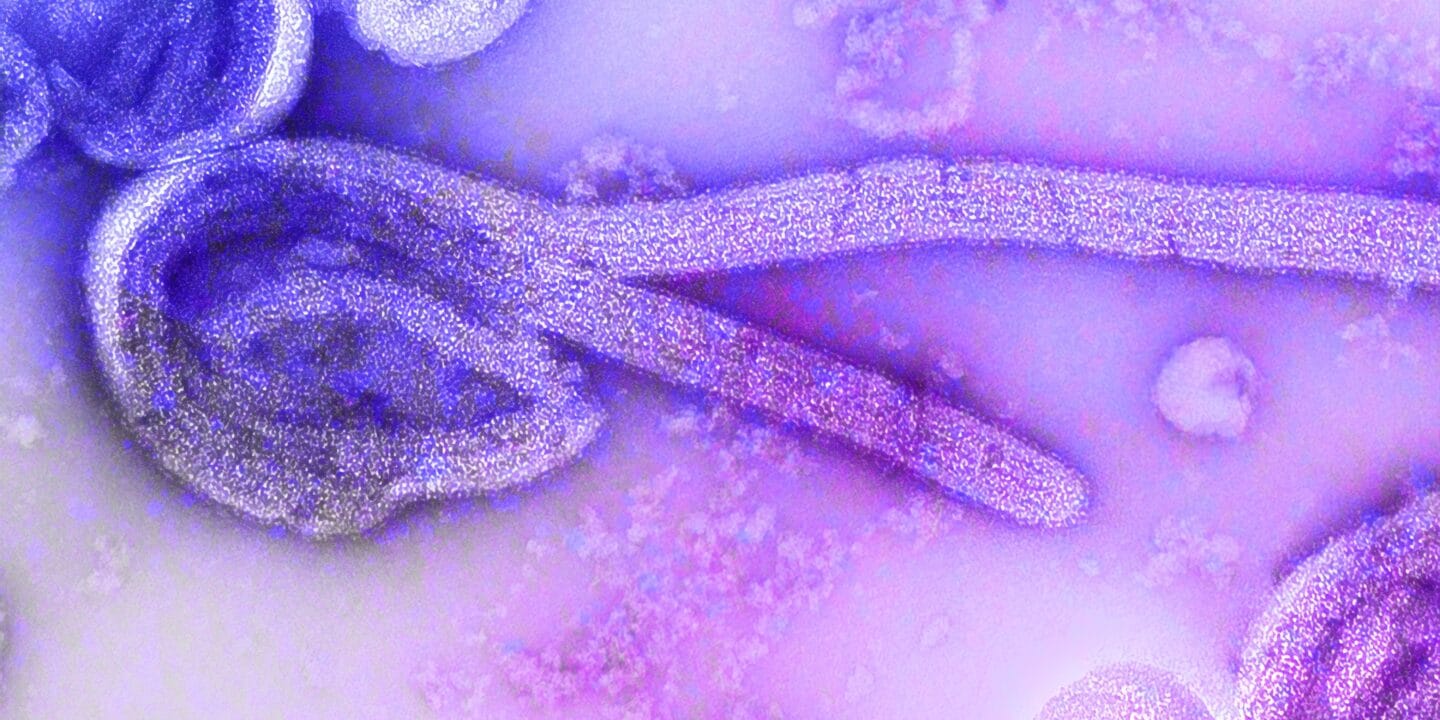

- Ebola Virus Disease [EVD]

Previously known as Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever, Ebola virus disease (EVD) is a serious, often deadly illness if left untreated. The Ebola virus was initially identified in 1976 along the Ebola River in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The viral family Filoviridae comprises three genera: Ebolavirus, Cuevavirus, and Marburgvirus.

Six species of Ebola Virus

- Bombali

- Reston

- Taï Forest

- Sudan

- Bundibugyo

- Zaire.

According to viral and epidemiologic data, the Ebola virus existed before any documented outbreaks. Direct contact with wildlife (such as bushmeat consumption), encroachment into forested regions, and population increase may have aided the spread of the Ebola virus.

Outbreaks

Since its discovery, EVD has resurfaced on a periodic basis, infecting people in various African nations. The 2014-2016 West African Ebola outbreak was the largest since the virus was identified in 1976, with 28,610 confirmed and probable cases and 11,308 fatalities. The disease began in Guinea and spread across borders to Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Another huge outbreak occurred in Uganda’s Gulu, Mbarara, and Masindi districts at the beginning of the century (2000-2001), infecting 425 people and killing 53% of them. Having contact with ill family members, providing medical care to Ebola patients without proper personal protective measures, and attending funerals of EVD victims were the most significant risks linked with these outbreaks.

Transmission

Fruit bats of the Pteropodidae family are thought to be natural hosts of the Ebola virus. Ebola spreads to the human species by direct contact with the secretions, organs, blood, or other body fluids of infected animals such as nonhuman primates (chimps, gorillas, monkeys), fruit bats, porcupines, or forest antelopes found unwell or dead, or in the jungle. This is known as a spillover event. The infection then spreads from person to person, eventually affecting a wide population.

Ebola spreads from person to person by direct contact (via mucous membranes or broken skin) with:

- Ebola-infected or deceased person’s bodily fluids or blood

- Objects contaminated with bodily fluids (such as vomit, feces, or blood) from an Ebola patient or the body of an Ebola patient who died.

An individual can only spread EVD to others after developing Ebola symptoms, and they remain infectious as long as their blood contains the virus.

Risk Groups

The following are the key risk categories identified:

- Healthcare personnel offering Ebola treatment without proper personal protective equipment

- Attendees of burial ceremonies for Ebola hemorrhagic fever victims

- Individuals who have contact with the diseased’s family members.

EVD and pregnancy/breastfeeding

Pregnant women who contract Ebola and recuperate could still harbour the virus in their breastmilk or pregnancy-related fluids and tissues. This increases the danger of spreading to the baby they are carrying as well as to others.

Women who become pregnant after having survived EVD are not in danger of passing the infection on to their children. If an Ebola-infected nursing mother desires to continue breastfeeding, she should be encouraged. However, her breast milk must be screened for Ebola before she can begin.

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms might present from around 2 to 21 days following viral exposure, with an average of 8 to 10 days. As the disease progresses, signs and symptoms often proceed from “dry” symptoms (such as weariness, pains, fever, and aches) to “wet” symptoms (such as vomiting and diarrhea).

Ebola’s primary signs and symptoms frequently involve one or more of the following:

- Fever

- Sore throat

- Appetite loss

- Weakness and exhaustion

- Pains and aches, such as joint and muscle pain and a strong headache

- Gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal discomfort, vomiting, and diarrhea.

- Unexplained bleeding, hemorrhaging or bruising (for example, blood in the stools or oozing from the gums).

- Laboratory results show low white blood cell and platelet counts and increased liver enzymes.

Additional symptoms may include hiccups, a rash on the skin, and red eyes (late-stage).

Diagnosis

Ebola’s signs and symptoms are identical to those of other infectious illnesses such as meningitis, typhoid fever, and malaria, making diagnosis challenging.

To establish if Ebola is a potential diagnosis, a combination of symptoms indicative of Ebola and probable exposure to EVD within 21 days before the beginning of signs and symptoms must occur. The virus can be detected in the blood after the onset of symptoms, although it may not be recognized for the first three days. Because of its capacity to identify low amounts of Ebola virus, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is one of the most widely utilized diagnostic procedures.

Other approaches, based on identifying antibodies against the virus, are utilized to confirm a patient’s Ebola virus exposure and infection.

Treatment

Supportive care

Whether or not other treatments are given, early provision of fundamental interventions can dramatically enhance the odds of survival:

· Rehydration by intravenous or oral fluids

· Medicine to help with blood pressure, nausea, diarrhea, fever, and discomfort.

· Treat any further infections that arise.

Definitive treatment

The US Food and Drug Administration authorized two drugs for the treatment of Zaire ebolavirus (Ebolavirus) disease in adults and children in late 2020:

1. Inmazeb™ -made up of three monoclonal antibodies.

2. Ebanga™ -a single monoclonal antibody.

Ebola Vaccines

On December 19, 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized the Ebola vaccine rVSV-ZEBOV (Ervebo®). This is the first Ebola vaccine to be authorized by the FDA. It is administered as a single dose and is safe and effective against the Zaire ebolavirus, which has caused the greatest and deadliest Ebola epidemics to date.

The European Medicines Agency announced in May 2020 authorized a 2-component vaccine named Zabdeno-and-Mvabea for anyone aged one year and above.

The vaccine is given in two doses: Zabdeno is given initially, followed by Mvabea roughly eight weeks later. As a result, this preventive 2-dose regimen is not appropriate for an epidemic response where urgent protection is required.

Prevention and Control

If a person exhibits symptoms of Ebola and has a history of possible exposure, they should be isolated, and public health authorities should be alerted.

Monitoring and contact tracing, case management, a strong laboratory service, social mobilization, and safe burials are all important components of effective outbreak control. Community involvement is also critical to the successful containment of epidemics.

Promoting public knowledge of Ebola risk factors and preventative actions (including vaccination) that individuals may take is an effective method of limiting human transmission.

Healthcare providers should always take routine precautions when caring for patients, irrespective of their suspected diagnosis.

Among these

- Basic hand hygiene (using alcohol-based hand sanitizer, soap, and water)

- Wearing personal protection equipment (to avoid splashes or other contacts with infected materials)

- Safe injection procedures.

Written by Dr Samuel Irungu