Emphysema is a progressive lung disease that falls under the umbrella of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). It is characterized by the abnormal enlargement of the airspaces (alveoli) distal to the terminal bronchioles, leading to a loss of elastic recoil, destruction of lung tissue, and subsequent airflow limitation.

Pathophysiology

- Destruction of Alveoli:

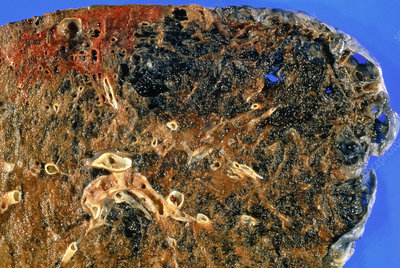

- In emphysema, the walls between the alveoli become damaged and are destroyed, leading to the formation of larger, less efficient airspaces. This reduces the surface area available for gas exchange.

- Loss of Elastic Recoil:

- The destruction of elastin fibers in the lung tissue results in a loss of elastic recoil, making it difficult for the lungs to expel air. This leads to air trapping, particularly during expiration.

- Airflow Limitation:

- As air becomes trapped in the lungs, it results in hyperinflation and reduces the ability to take in fresh air, causing progressive airflow limitation.

- Increased Compliance:

- The lungs become more compliant but less able to effectively exchange gases. This leads to hypoxemia (low oxygen levels) and hypercapnia (elevated carbon dioxide levels).

- Inflammatory Response:

- Chronic exposure to irritants, particularly cigarette smoke, triggers an inflammatory response in the lungs, leading to further destruction of lung tissue and exacerbation of symptoms.

Types of Emphysema

- Centriacinar Emphysema:

- Primarily affects the central parts of the acinus (the functional unit of the lung). It is commonly associated with cigarette smoking and is often more pronounced in the upper lobes.

- Panacinar Emphysema:

- Involves uniform destruction of the alveoli across the acinus, affecting the lower lobes more prominently. It is often associated with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

- Distal Acinar Emphysema (Paraseptal Emphysema):

- Affects the distal alveolar regions and is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax. It typically occurs in the upper lobes and is characterized by the presence of cyst-like spaces.

Clinical Presentation

- Symptoms:

- Dyspnea: Progressive shortness of breath, initially occurring with exertion and later at rest as the disease advances.

- Chronic Cough: Less common than in chronic bronchitis but may occur, especially in later stages.

- Sputum Production: Not as prominent as in chronic bronchitis; may be present in exacerbations.

- Wheezing: A high-pitched whistling sound during breathing due to airway narrowing.

- Fatigue: Reduced exercise tolerance and increased fatigue due to compromised lung function.

- Signs:

- Physical Examination:

- Barrel chest: Increased anterior-posterior diameter of the chest due to hyperinflation.

- Use of accessory muscles for breathing in advanced cases.

- Decreased breath sounds, prolonged expiration, and wheezing may be noted on auscultation.

- Cyanosis: Bluish discoloration of the lips or fingertips may occur in advanced stages, particularly during exacerbations.

- Physical Examination:

Diagnosis

- Medical History:

- A thorough history of smoking, occupational exposures, family history, and symptoms is essential.

- Physical Examination:

- Assessment of respiratory function, signs of respiratory distress, and comorbidities.

- Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs):

- Spirometry: Key diagnostic test. A post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio of < 0.70 confirms the presence of airflow limitation, indicating COPD. In emphysema, FEV1 is typically reduced more than FVC.

- Imaging Studies:

- Chest X-ray: May show hyperinflation, flattened diaphragm, and increased retrosternal airspace.

- CT Scan: High-resolution CT is more definitive, showing areas of emphysema, destruction of lung parenchyma, and increased airspace.

- Arterial Blood Gas Analysis:

- May reveal hypoxemia and hypercapnia, especially during exacerbations.

- Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Levels:

- In young patients or those with a family history, testing for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency may be indicated.

Management

- Smoking Cessation:

- The most critical intervention for slowing disease progression. It significantly improves symptoms and lung function.

- Medications:

- Bronchodilators:

- Short-acting bronchodilators (SABAs and SAMAs) for rapid relief of symptoms.

- Long-acting bronchodilators (LABAs and LAMAs) for regular use to improve lung function and reduce symptoms.

- Inhaled Corticosteroids (ICS):

- Used in combination with LABAs for patients with frequent exacerbations or significant eosinophilic inflammation.

- Phosphodiesterase-4 Inhibitors:

- Roflumilast can be prescribed for patients with severe emphysema and frequent exacerbations to reduce inflammation.

- Bronchodilators:

- Pulmonary Rehabilitation:

- A comprehensive program that includes exercise training, education, and support to improve functional status and quality of life.

- Oxygen Therapy:

- Indicated for patients with chronic hypoxemia (PaO2 < 55 mmHg or oxygen saturation < 88%). Long-term oxygen therapy can improve survival and quality of life.

- Management of Exacerbations:

- Exacerbations are often triggered by respiratory infections or environmental factors. Management includes:

- Bronchodilator Therapy: Increased frequency and dosage of bronchodilators.

- Corticosteroids: Oral or systemic corticosteroids for reducing inflammation during exacerbations.

- Antibiotics: Indicated for bacterial infections or significant purulent sputum production.

- Exacerbations are often triggered by respiratory infections or environmental factors. Management includes:

- Surgical Options:

- In selected patients with severe emphysema and significant hyperinflation, surgical options such as lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS) or lung transplantation may be considered.

Prognosis

- The prognosis for emphysema varies widely depending on factors such as:

- Smoking status

- Severity of airflow limitation

- Presence of comorbidities (e.g., cardiovascular disease)

- Adherence to treatment and lifestyle changes

- Regular follow-up and monitoring are essential to manage symptoms, prevent exacerbations, and improve quality of life.

Conclusion

Emphysema is a progressive lung disease characterized by the destruction of alveoli, loss of elastic recoil, and airflow limitation. Effective management strategies, including smoking cessation, medication adherence, and pulmonary rehabilitation, can significantly improve patient outcomes and quality of life. Regular monitoring and patient education are crucial for managing emphysema and preventing complications.