- Home

- INTERNAL MEDICINE

- Cholera

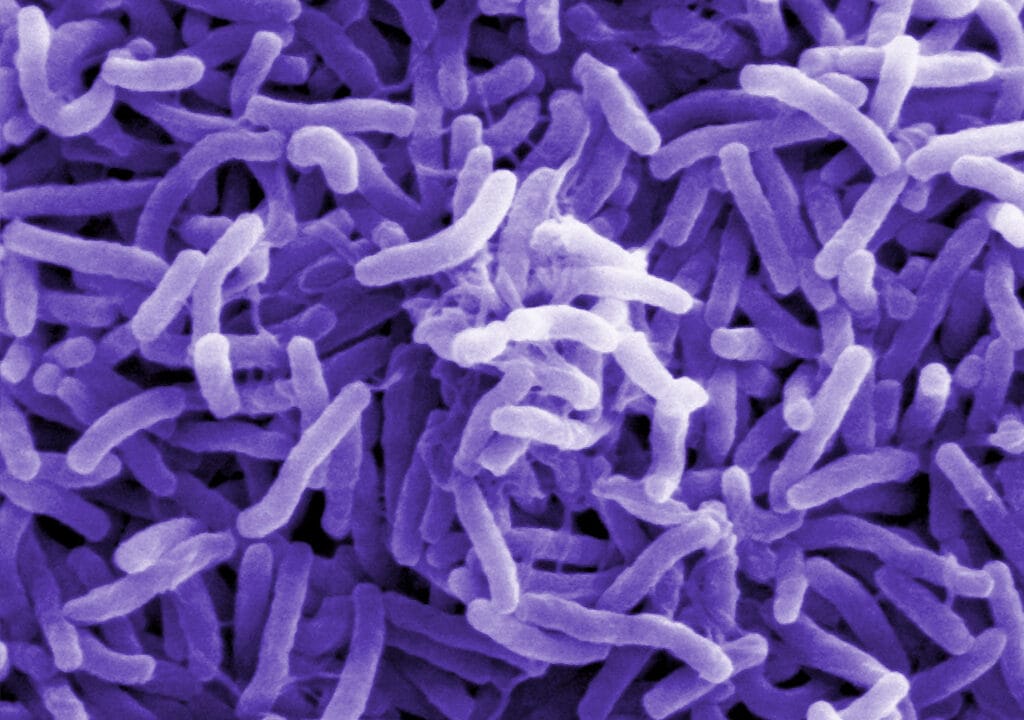

Cholera is an acute infectious disease caused by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with Vibrio cholerae, a Gram-negative, comma-shaped bacterium. It leads to profuse, watery diarrhea, which can rapidly result in severe dehydration and death if left untreated.

Cholera outbreaks often occur in areas with inadequate water treatment, poor sanitation, and insufficient hygiene, posing significant public health challenges.

Microbiology

- Causative agent: The main pathogenic strains are Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139, which produce cholera toxin. The O1 serogroup is further classified into two biotypes:

- Classical biotype: Historically responsible for several pandemics.

- El Tor biotype: More prevalent in recent outbreaks and associated with a higher carrier state.

- Non-O1 and non-O139 serogroups: Rarely cause cholera epidemics but can still lead to sporadic cases of gastroenteritis.

- Virulence factors:

- Cholera toxin (CTX): A protein complex that stimulates secretion of electrolytes and water into the intestinal lumen, causing severe diarrhea.

- Toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP): A surface structure that facilitates bacterial colonization of the small intestine.

Epidemiology

- Global Impact: Cholera affects millions worldwide, with an estimated 2.9 million cases and 95,000 deaths annually. It is endemic in regions of Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East, with periodic outbreaks linked to poor living conditions.

- Pandemic history: There have been seven cholera pandemics since the early 19th century. The current pandemic, caused by the El Tor biotype, began in Indonesia in 1961 and continues to affect regions worldwide.

- Risk Factors:

- Living conditions: Crowded environments, refugee camps, slums, or areas affected by natural disasters or conflicts.

- Water sources: Dependence on untreated or poorly treated water sources.

- Hygiene practices: Lack of proper sanitation and handwashing facilities.

Transmission

- Mode of transmission: Cholera is primarily spread through the fecal-oral route. Contaminated water is the most common vector, but food contamination can also occur.

- Human reservoirs: Infected individuals can shed large amounts of bacteria in their stool, especially in the early stages of the disease. Asymptomatic carriers can also play a role in transmission.

- Environmental reservoirs: V. cholerae can survive in aquatic environments, particularly in brackish water and estuaries, where it can associate with plankton and other marine life.

Pathophysiology

- Bacterial ingestion and colonization: After ingestion, V. cholerae must survive the acidic environment of the stomach before colonizing the small intestine. It attaches to the epithelial cells using the TCP.

- Production of cholera toxin: Once colonized, the bacteria produce cholera toxin, which activates adenylate cyclase via the Gs protein, leading to an increase in intracellular cAMP.

- Electrolyte and fluid loss: Elevated cAMP causes the efflux of chloride ions into the intestinal lumen through the CFTR channels, followed by sodium and water, resulting in the characteristic profuse, watery diarrhea.

Clinical Manifestations

- Incubation period: Ranges from a few hours to five days, with a median of 2-3 days.

- Symptoms:

- Watery diarrhea: Typically described as “rice-water stools” due to its pale and milky appearance, with a fishy odor.

- Vomiting: May precede or accompany diarrhea, contributing to fluid loss.

- Severe thirst and dehydration: Develops rapidly due to massive fluid loss, with the potential for hypovolemic shock.

- Muscle cramps: Result from electrolyte disturbances, particularly potassium loss.

- Mild cases: May present with non-specific symptoms or self-limited diarrhea, while severe cases can cause life-threatening dehydration within hours.

- Signs of dehydration (classified as mild, moderate, or severe):

- Mild dehydration: Thirst, dry mouth, slightly decreased urine output.

- Moderate dehydration: Tachycardia, hypotension, sunken eyes, decreased skin turgor, oliguria.

- Severe dehydration: Profound lethargy, rapid and weak pulse, cold extremities, cyanosis, anuria, and eventual loss of consciousness.

Diagnostic Approach

- Clinical diagnosis: In areas with a known outbreak, the diagnosis is primarily clinical, based on the presentation of acute watery diarrhea and dehydration.

- Laboratory diagnosis:

- Stool culture: The gold standard for confirming cholera. Specimens should be collected early and cultured on selective media such as thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose (TCBS) agar.

- Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs): Detect V. cholerae antigens in stool and can be used for preliminary diagnosis in resource-limited settings.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): Highly sensitive and specific, used for detecting V. cholerae DNA in stool samples.

- Dark-field microscopy: May reveal the characteristic motility of vibrios in fresh stool, but is less commonly employed.

Differential Diagnosis

- Other infectious causes of acute gastroenteritis: Rotavirus, norovirus, enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), Cryptosporidium, Shigella, and Salmonella.

- Non-infectious causes of diarrhea: Inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, irritable bowel syndrome.

- Food poisoning: Especially with toxins produced by Staphylococcus aureus or Bacillus cereus, which may cause vomiting and diarrhea.

Management

- Rehydration Therapy:

- Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS): The cornerstone of treatment for mild to moderate dehydration. WHO-recommended ORS contains 75 mEq/L sodium, 75 mmol/L glucose, 20 mEq/L potassium, and 65 mEq/L chloride. Aim to replace lost fluids with ORS based on weight and severity of dehydration.

- Intravenous (IV) fluids: Indicated for severe dehydration or shock. Ringer’s lactate is preferred due to its balanced electrolyte composition.

- Initial fluid bolus: Administer 30 mL/kg of body weight over 30 minutes, followed by 70 mL/kg over the next 2.5 hours.

- Maintenance fluids: Continue based on ongoing stool losses and clinical status, using ORS if the patient can tolerate oral intake.

- Monitoring: Evaluate the patient’s hydration status hourly in the initial stages and adjust fluid administration as needed. Watch for signs of overhydration (e.g., pulmonary edema) or underhydration.

- Antibiotic Therapy:

- Indications: Antibiotics are recommended for patients with severe cholera to reduce the duration and volume of diarrhea and bacterial shedding.

- Commonly used antibiotics:

- Doxycycline: 300 mg single dose for adults, or 2-4 mg/kg for children.

- Azithromycin: 1 g single dose for adults, 20 mg/kg for children.

- Ciprofloxacin: 1 g single dose for adults, or 15 mg/kg for children.

- Choice of antibiotic: Depends on local resistance patterns. Azithromycin is often preferred in areas with known tetracycline resistance.

- Adjunctive Therapy:

- Zinc supplementation: Especially recommended for children, as it can reduce the duration and severity of diarrhea.

- Dosing: 20 mg/day for children older than six months, and 10 mg/day for infants younger than six months for 10-14 days.

- Antimotility agents: Generally not recommended due to the risk of exacerbating toxin retention.

- Zinc supplementation: Especially recommended for children, as it can reduce the duration and severity of diarrhea.

Complications

- Severe dehydration and hypovolemic shock: Can lead to acute renal failure, electrolyte disturbances, and multi-organ dysfunction.

- Electrolyte imbalances: Hypokalemia, hyponatremia, and metabolic acidosis are common due to loss of potassium and bicarbonate in the stool.

- Mortality: If untreated, severe cholera has a mortality rate exceeding 50%, but with proper treatment, the rate can be less than 1%.

Prevention and Control

- Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH):

- Ensure access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation facilities.

- Promote handwashing with soap and safe food handling practices.

- Implement water chlorination programs and safe disposal of human waste.

- Oral Cholera Vaccines (OCVs):

- Types: Killed whole-cell vaccines (e.g., Dukoral, Shanchol, and Euvichol) provide short-term protection against cholera.

- Indications: Recommended for people living in endemic areas, during outbreaks, and for travelers to high-risk regions.

- Dosing regimen: Typically, two doses are administered 1-6 weeks apart, with booster doses required for prolonged protection.

- Surveillance and Outbreak Response:

- Early detection and reporting of cholera cases are critical for outbreak management.

- Rapid implementation of public health measures, including mass vaccination and WASH interventions, can curb transmission.

Prognosis

- With timely and adequate rehydration therapy, the prognosis for cholera patients is excellent, with a mortality rate below 1%.

- However, delays in treatment, particularly in areas with limited healthcare access, significantly increase the risk of death from dehydration.