- Home

- GYNECOLOGY/OBSTETRICS

- Obstetrics

- Placental abruption

Placental abruption, also known as abruptio placentae, is the premature separation of the placenta from the uterine wall before delivery. It can lead to significant maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality, depending on the severity of the detachment.

Epidemiology

- Incidence: The incidence of placental abruption ranges from 1% to 3% of all pregnancies.

- Risk Factors:

- Previous history of placental abruption.

- Maternal hypertension (chronic or gestational).

- Trauma (e.g., motor vehicle accidents, falls).

- Cigarette smoking and substance abuse (cocaine).

- Advanced maternal age (≥35 years).

- Multiple gestations.

- Uterine anomalies (e.g., fibroids).

- History of preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM).

- Thrombophilia or coagulation disorders.

Etiology

The precise etiology of placental abruption remains unclear; however, several contributing factors have been identified:

- Maternal Vascular Issues:

- Hypertensive disorders lead to vascular changes that may predispose to abruption.

- Uterine Overdistension:

- Conditions such as multiple gestations or polyhydramnios can stretch the uterus and compromise placental attachment.

- Trauma:

- Physical trauma can directly disrupt the placental attachment.

- Cigarette Smoking and Drug Use:

- Smoking has been linked to an increased risk of placental abruption, possibly due to its effects on placental blood flow.

- Infections:

- Chorioamnionitis may be associated with increased risk.

Pathophysiology

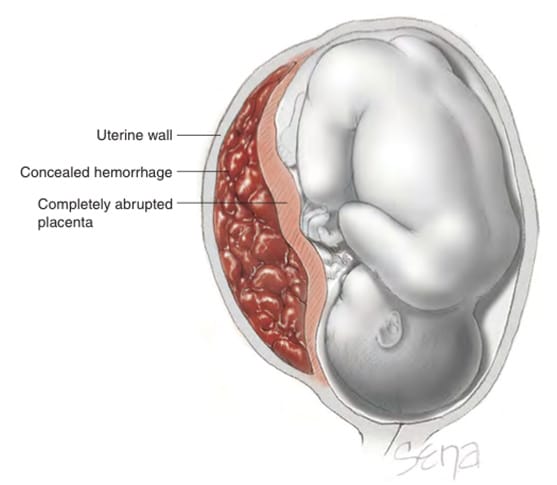

- The placenta is normally attached to the uterine wall via the trophoblasts that invade the endometrium. In placental abruption, there is a disruption of this attachment, leading to bleeding and separation.

- The separation may be partial or complete and can occur at any point during the third trimester, but is most common in the late second or third trimester.

- This separation results in bleeding into the maternal compartment and can compromise fetal blood supply, potentially leading to fetal distress or demise.

Clinical Features

- Symptoms:

- Vaginal Bleeding: May be visible or concealed (not immediately apparent).

- Abdominal Pain: Sudden-onset, severe pain often accompanied by uterine tenderness.

- Uterine Contractions: Frequent contractions may occur.

- Fetal Movement Changes: May report decreased fetal movements.

- Signs:

- Uterine hypertonicity or rigidity on examination.

- Signs of fetal distress (abnormal fetal heart rate patterns).

- Hypotension or signs of shock in the mother if bleeding is significant.

Diagnosis

- Clinical Diagnosis:

- The diagnosis is primarily clinical based on the triad of bleeding, abdominal pain, and uterine tenderness.

- Ultrasound:

- Transabdominal Ultrasound: Useful for identifying placental location and ruling out placenta previa; may show retroplacental hematoma but is not always definitive.

- Transvaginal Ultrasound: More sensitive for detecting retroplacental hematomas and assessing placental detachment.

- MRI:

- In rare cases, MRI may be considered for further evaluation if ultrasound findings are inconclusive.

- Laboratory Tests:

- CBC: To assess for anemia and hemoconcentration.

- Coagulation Studies: If significant bleeding is suspected.

Classification

Placental abruption can be classified based on the degree of separation:

- Mild Abruption:

- Less than 25% of the placenta is detached.

- Usually manageable with monitoring.

- Moderate Abruption:

- 25% to 50% separation.

- Requires close monitoring and potential intervention.

- Severe Abruption:

- Greater than 50% separation or complete abruption.

- Associated with significant maternal and fetal risk.

Management

Antepartum Management

- Stabilization:

- Initiate IV access and fluid resuscitation if signs of hypovolemia or shock are present.

- Monitor vital signs and fetal heart rate continuously.

- Hospitalization:

- Admit for monitoring, especially if significant bleeding is present or if the patient is less than 34 weeks gestation.

- Corticosteroids:

- Administer corticosteroids (e.g., betamethasone) for fetal lung maturity if preterm delivery is anticipated (usually <34 weeks).

- Delivery Considerations:

- If the abruption is severe, immediate delivery (typically via cesarean section) is indicated, especially if fetal distress or maternal instability occurs.

- In cases of mild to moderate abruption with stable maternal and fetal conditions, delivery may be delayed until closer to term, provided that the mother and fetus are monitored closely.

Delivery Management

- Mode of Delivery:

- Cesarean delivery is often preferred in cases of significant abruption or fetal distress.

- Vaginal delivery may be possible if the abruption is mild, and there are no signs of fetal distress.

- Anesthesia:

- Regional anesthesia is preferred but may need to be adjusted based on the urgency of the situation.

Postpartum Management

- Monitoring for Hemorrhage:

- Monitor for postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony or retained products of conception.

- Counseling and Follow-up:

- Discuss potential risks in future pregnancies, including the possibility of recurrent abruption and increased cesarean delivery rates.

Complications

- Maternal Complications:

- Severe hemorrhage leading to hypovolemic shock.

- Coagulopathy or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

- Increased risk of hysterectomy.

- Fetal Complications:

- Preterm birth.

- Fetal growth restriction (FGR).

- Stillbirth or neonatal death.

Prognosis

The prognosis for women with placental abruption varies widely depending on the severity of the abruption, timing of diagnosis and intervention, and the presence of associated risk factors. Early recognition and appropriate management significantly improve maternal and fetal outcomes.